How embracing poka-yoke philosophy led to better quality outcomes

The Problem

A few times a year, we were scrapping jobs due to issues in our developing process. It wasn’t enough that it would make or break our business, but it could be disruptive.

Development occurs in a room without any UV light. Though well lit, the development room is very yellow. It can take some getting used to.

The development process requires the removal of very thin, transparent sheets of mylar from the top and bottom of the dryfilm. Sometimes, our operators failed to remove one or both of these mylar sheets. When this occurred, we had to scrap the parts.

One Way To Solve It

At this point, many companies might try to address the errors with the employees directly. Options might include better training, warnings, performance improvement plans, or even replacing the employee.

But such solutions are only temporary at best. They don’t solve the problem, they provide an incentive for an employee to try to avoid the problem. Managing problems in this way, one employee at a time, can become resource intensive and usually doesn’t scale very well.

But what if the problem isn’t the employee? What if the problem is the process?

Poka-Yoke And Continuous Improvement

After World War II, Japan sought to bolster its manufacturing sector. Industry leaders there partnered with American management consultants such as W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran to help propel Japanese manufacturing forward.

This would become the foundation of the Lean Manufacturing philosophy, which we embrace at Flex Interconnect Technologies.

In his System of Profound Knowledge, Deming stated that 94% of variations observed in workers’ performance are the result of systems, not people, and that people cannot perform better than the system allows.

To get better, more consistent outcomes, it’s up to managers to improve systems.

That’s where poka-yoke comes in. Poka-yoke is a Japanese term meaning “mistake-proofing.” The poka-yoke philosophy, applied to manufacturing, means designing systems and processes in a way that prevents errors and eliminates the possibility of mistakes or variances.

At Flex Interconnect Technologies, our functional teams meet weekly with a focus on poka-yoke and continuous improvement. Amongst themselves, our teams discuss issues and problem areas affecting their work, and come up with their own solutions.

Solving The Mylar Sheet Problem

From one such meeting, our team solved the issue of the mylar sheets.

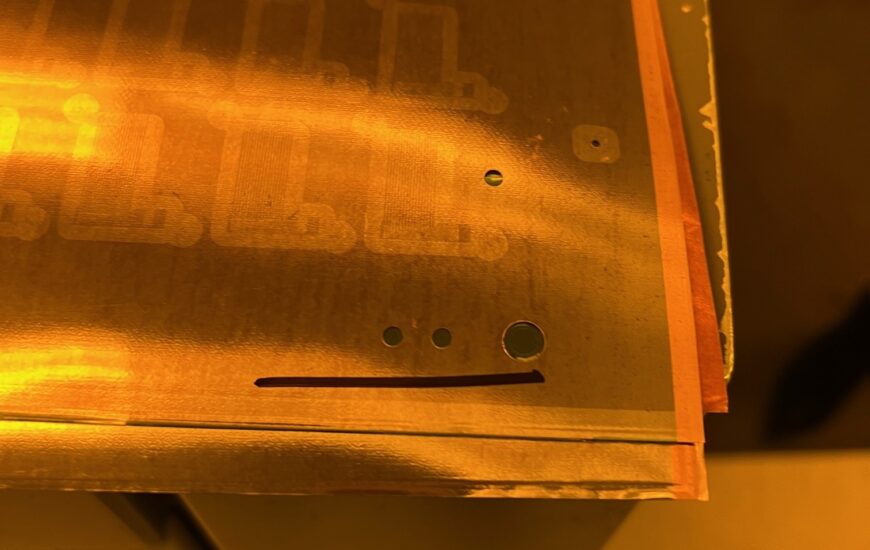

Today, we mark the mylar sheet with a black sharpie after imaging. We consistently mark the sheets in the same corner, aligned with where we have offset drilled targets in our panels to assist with orientation.

Now our operators know to look for the black mark before sending panels on to the developer. When they see a black mark, they know to remove the mylar sheet. If there’s no black mark, the panel is ready for development.

In the three years since implementing this change to our system, we haven’t scrapped a single panel due to the issue with the mylar sheets.